Political writing and political reading.

Politics is concerned with ideas about how we live, power, class, inequality, social and economic relations and how they change over time. Writing also deals with how we live, and we can think of all writing as political, whether explicitly or not, and we can think of all reading as political as well. Each writer and each reader brings their own political sensibility to a text.

Novels can be political interventions, representing political ideas and social, economic and political debates and controversies. Within a novel, these can be embedded in narrative, character, plot, description and observation. A novel can help to make social and political change possible, broaden the scope of possibility, change people’s consciousness and their ways of thinking.

Some writing has very explicit political purposes and clear political impacts. The most obvious example is the genre of engaged, polemical, campaigning writing or journalism such as Emile Zola’s ‘J’Accuse…’, but I’ve chosen here to concentrate on Zola’s fiction. There is a lot to read and a lot to say about the politics of Zola’s work, so this is a very partial, provisional and personal political reading.

Zola (1840-1902) in his time.

The history of France in the 19th century is one of revolutions, counter-revolutions and coups d’état. Influential ideologies include nationalism, legitimism, Orleanism, Bonapartism, bourgeois and proletarian republicanism, socialism, utopian socialism, Marxism and anarchism. In common with other European countries, 19th century France experiences the development of industrial capitalism, urbanisation, factory work, new forms of poverty, inequality, class identity, working class self-organisation, trade unionism, exploitation, colonialism, imperialism, racism and antisemitism.

Zola aims to present all of this with authenticity, naturalism, realism, respect for the truth and empathy. Amongst other things, he wants to represent working-class lives and struggles and show the relationship between individual experience and great social, economic and political events at the system level.

What is clear about Zola’s political standpoint is that he is a committed republican. Republicanism covers a variety of political currents, but broadly includes all those who identify with the 1789 revolution and the values of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. It is an anti-monarchist and anti-clerical position, opposed to the church’s influence on society, and education in particular.

Zola combines this commitment to republicanism with an understanding of its contradictions. His republicanism points towards socialism, and he admired the courage of the republicans who stood up against the crimes of the Second Empire. It was the ‘red republicans’ who aroused his admiration most and he was contemptuous of those who adopted or abandoned republican principles to suit their own interest.

The influence of Balzac.

The realist novel in France begins with Honoré de Balzac’s ‘Comedie Humaine’, a series of interconnected novels aiming to depict the different classes, professions and regions of post-revolutionary France. In the new bourgeois order, money starts to substitute for many of the institutions that define the social order and Balzac presents the social relations of this new order in granular detail. He wants us to know everything about how his characters live, what they wear, how much they earn as well as what they say and do.

The young Zola greatly admired Balzac because of the devastating way he portrayed the bourgeoisie.

“He showed a hundred times over the narrow, limited spirit of this class… All the bourgeois of Balzac, with a very few exceptions, are selfish, ambitious beasts who patiently watch and eagerly hunt their quarry.”

But Balzac was a monarchist and a devout Catholic. His criticism of bourgeois society is based on pre-capitalist values such as community and humanity. As Zola points out, if there was a radical message in Balzac’s novels, it was there despite Balzac:

“Here is a man who… bowed down every day before royalty and Catholicism… And today all we perceive in his work is a powerful revolutionary inspiration… On his flag, where he wrote: Royalty, Catholicism, our children will read the word: Republic

Who else is writing politically around this time?

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) does portray working class characters but they generally lack depth or credibility, and are often figures of ridicule. His only depiction of trade unions and strikes, in ‘Hard Times’ (1854), shows little understanding of workers’ organisation and solidarity. The nearest to a working-class hero is the hopeless Stephen Blackpool who is praised as a strike breaker.

Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865) in ‘North and South’, serialised soon after ‘Hard Times’ in Dickens’ ‘Household Words’, offers a far more balanced and empathetic view of the motivation of striking workers, from the perspective of a middle-class outsider.

Jules Vallès (1832-1885) wrote a trilogy of semi-autobiographical novels: ‘L’Enfant’ (1879), ‘Le Bachelier’ (1881) and L’Insurgé (1886). He was the editor of ‘Le Cri du Peuple’ campaigning newspaper and was encouraged in his writing by Zola. He fought as a Communard in 1871 and subsequently went into exile for a period after being sentenced to death.

Margaret Harkness (1854-1923), also a campaigning journalist and social reformer, wrote ‘A City Girl’ and ‘Out of Work’ which are serious attempts to see poverty and exploitation through the eyes of working-class characters and communities.

Another key figure of the period produced no fiction but was a prolific pamphleteer and astute political commentator. Karl Marx (1818-1883) was a polemical journalist with a vivid style, a memorable turn of phrase and a passionate enthusiasm for the writing of Cervantes, Dante, Pushkin, Schiller, Aeschylus and Sterne. He wrote about French politics in real time from 1848 to 1871, responding far more rapidly than Zola to the same events.

As well as being an active propagandist, Marx also wanted to explain the deeper systemic historic tendencies and social relations of the contemporary world. His key writings on France include: ‘The Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850’ about the origins of the upheavals, ‘The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon’ about the subsequent coup d’état of 1851, and ‘the Civil war in France’ about the Commune of 1871.

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honoured disguise and borrowed language.

Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce… the nephew for the uncle…”

Karl Marx, ‘The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon’ (1852)

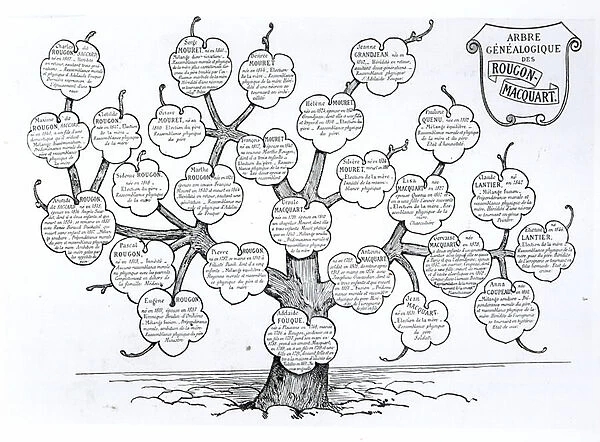

The Rougon-Macquart cycle

The Rougon-Macquart cycle is Zola’s attempt to create a panorama of a whole society over a 20 year period and through 20 separate novels, dissecting every level of human experience and type of social relation. It’s a phenomenal political intervention and analysis of an emerging capitalist system.

The series is framed by Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état and the regime’s defeat by the Prussians and the Paris Commune but we need to go back to the revolutions of 1848, or even 1789, to better understand the context. Zola understood that 1848 was the last point at which the bourgeoisie had been genuinely revolutionary. He wrote:

“The bourgeoisie betrays its revolutionary past to try to safeguard its capitalist privilege and remain the ruling class. Having taken power, it does not want to pass it on to the people. It ceases to move. It allies with reaction, with clericalism, with militarism. I must bring out the vital, decisive idea that the bourgeoisie has ended its role, that it has gone over to reaction to preserve its wealth and power, and that all hope for the energy of tomorrow is in the people.”

I’ve selected nine Rougon Macquart novels, under half of the series, to give a flavour of what a political reading can reveal. These are not synopses of the novels but an introduction to some of the key political themes of this monumental work.

La Fortune des Rougon (1871)

This is the origin story for the whole series and it reveals the class distinctions and antagonisms of French society from the outset, the fictional provincial town of Plassans, based on Aix en Provence, where Zola grew up. Plassans is geographically segregated into “three distinct independent parts”: Saint-Marc, the district of the nobility a “sort of miniature Versailles” with large square houses and extensive gardens; the new town, “a sort of parallelogram to the north-east; where the well-to-do, those who have slowly amassed a fortune, and those engaged in the liberal professions, occupy houses set out in straight lines and coloured a light yellow;” and finally the old quarter with its “narrow, tortuous lanes bordered with tottering hovels”

The novel also includes the sweet love story of Silvere Mouret and Miette Chantegreil, a tale of idealistic outsiders carried along by republican fervour in opposing Louis-Napoleon’s coup d’état. They are the first in a line of rebels and would-be revolutionaries throughout the series whose sincere actions will not live up to their utopian hopes.

La Curée (1872)

‘La Curée’ depicts the wild speculation and profiteering which powered the ‘Haussmanisation’ of Paris which concentrated wealth into the hands of a powerful new class. The construction of the new boulevards which transformed the city also feed a chain of expropriation and corruption, from government and city officials to investors, developers and contractors. The urge to improve and modernize is not portrayed as evil, but here it has been corrupted to serve the wrong people.

The fluid, destructive force of capital is graphically described:

“This fortune which roared and overflowed like a winter torrent… a frenzy of money… The appetites let loose were satisfied at last, shamelessly, amid the sound of crumbling neighbourhoods and fortunes made in six months… The city had become an orgy of gold and women. Vice, coming from on high, flowed through the gutters and spread out.”

‘La Curée’ is also a story of the powerlessness and exploitation of women in the Second Empire. Towards the end of the story, the central character Renée sees herself in a mirror as she is, naked to the world. Despite having asserted her desires, exercised some freedom to make choices and dominate her lover, she has ultimately been violated and expropriated by men who get away with it. These men are guilty, their social and financial networks are guilty and the whole of Paris is guilty.

Le Ventre de Paris (1873)

In ‘Le Ventre de Paris’, Florent Quenu, a deported revolutionary from the 1848 uprising, returns illegally to his brother’s home in Paris eight years later, gets involved in republican plotting and is eventually betrayed to the police by his sister-in-law, Lisa Quenu, whose politics is summed up by her statement: “I support the government which is good for trade. If it’s doing wicked deeds, I don’t want to know.” In his own words, Zola shows “what an amazing underside of cowardice and cruelty there is beneath the calm flesh of a bourgeois woman.”

Florent’s hapless plotting is depicted as motivated as much by the need for personal revenge on the system which has damaged him as by a genuine desire for political change.

L’Assommoir (1877)

A tale of the fall of respectable working-class characters into poverty and destitution through circumstances outside their control. Zola sets out the lesson of ‘L’Assommoir’ by advocating a programme of education, slum clearance and struggle against alcoholism; a reformist programme, but one that put him to the left of most of his contemporaries.

Zola was concerned, not with moralising about social phenomena, but with understanding their causes. The criticism of Zola was similar to that later directed at Orwell’s ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’, when he challenged left wing stereotypes of working-class virtue. In response to his critics, he said: “Are Gervaise and Coupeau idlers and drunkards? By no means. They become idlers and drunkards, which is quite a different thing.”

Here, Zola is not portraying the working class as a transformative agent of history, but as victims, brutalised and trapped by the system.

Jules Vallès, a leading figure in the Commune, now exiled in London, praised L’Assommoir: “M. Zola is a red in literature, a Communard of the pen.” Jules Guesde, later leader of the left within the French Socialist Party, commended Zola’s portrayal of workers under the Empire, “crushed by the heavy burden of the past, brutalised by excessive toil, dragged into alcoholism by overwork.”

Nana (1880)

‘Nana’ is a thoroughgoing exploration of the social nature of sex as commodity with the theme of class also running through it. Nana is a child of the slums, and her role is likened to that of a fly:

“… a fly the colour of sunshine which had flown up out of the dung, a fly which had sucked death from the carrion left by the roadside and now, buzzing, dancing and glittering like a precious stone, was entering palaces through the windows and poisoning the men inside, simply by settling on them.”

Nana brings death but is herself a victim of exploitation and patriarchy.

Pot-Bouille (1882)

In ‘Pot-Bouille’, Zola traces the fortunes of people living in a single apartment block and confronts the private life of the bourgeoisie, the futility and violence of their interpersonal and sexual relations.

In his notes for the novel, Zola made his intentions clear:

“To speak of the bourgeoisie is to make the most violent indictment that one can cast against French society … To show the bourgeoisie naked, after having portrayed the people, and to show it as more abominable, this class which sees itself as representing order and respectability … the bourgeoisie taking its pleasure and opposing all change. They vote out of self-interest to preserve their position. Hatred of new ideas, fear of the people, determination to stop the revolution at the point where they come to power. When they feel under threat, they all band together.”

Zola shows how the bourgeois family crushes women’s freedom and humanity, and treating them as commodities. For example, Madame Josserand is determined to find a husband for her not very ‘marriageable’ daughter, Berthe. When Berthe recounts how a well-placed prospect grabbed her violently, and she had responded by pushing him away. Instead of taking her side, her mother shouts that she has ruined her chances of marriage, and should have let the man do what he wanted so as to then trap him into marriage.

The other side of the coin is the story of the servant Adèle, forced to give birth in complete solitude, in fear and terrible suffering. Zola saw this as a clear indictment of the society that drove women into such situations.

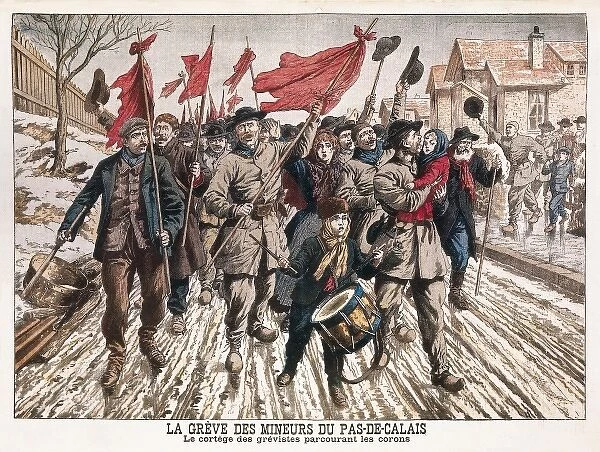

Germinal (1885)

‘Germinal’ is probably the major working-class novel of the 19th century. It draws on Zola’s extensive research into the exploitation of miners in northern France and is influenced by conversations Zola had with Turgenev about Anarchist challenges to Marx’s ideas. We follow Étienne Lantier on a journey through the working community that brings him face to face with violence and despair, without ever destroying his belief in a better world.

Étienne embodies the tension between leaders and masses in a working-class movement. He is a worker-intellectual, who reads socialist newspapers and pamphlets, and debates with the Russian anarchist, Souvarine. When the mine owners cut pay rates, a strike begins, and Etienne emerges as a leader. At a mass meeting of workers Etienne captures the mood of the crowd and makes the speech of his life. He is ‘tasting the heady wine of popularity’ and dreams of being the first working man to enter parliament.

Zola shows that working class leadership is not a fixed hierarchical relationship, but an ever-shifting relation. Zola draws out the importance of spontaneity, showing the gradual dawning of consciousness in struggle. He goes into some detail on tactics, such as the potential use of sabotage or flying pickets.

He also shows how ideas develop in the minds of the less articulate characters, bringing out the effect of a strike on those who have taken their situation for granted for years. Faced with the fact of struggle for the first time, they have to painfully think through the questions this raises.

Zola emphasizes the role of women miners and miners’ wives in the strike and rejects the conventional wisdom about the ‘weaker sex’ – his women are extraordinarily tough, notably the indomitable Maheude.

Zola portrays a microcosm of the late 19th-century labour movement, with articulate representatives of the main political currents in the First International prior to the Commune:

- Rasseneur, the reformist or evolutionary socialist, believing in negotiation rather than confrontation,

- Pluchart, the international socialist,

- Abbé Ranvier, the Christian socialist,

- Souvarine, the anarchist,

- Étienne, somewhere between the two, groping towards militant class struggle and a version of Marxism.

Souvarine, the refugee from Tsarist Russia, where he had tried unsuccessfully to blow up the Tsar’s train, views all trade union activity as futile and seeks “anarchy, the end of everything, the whole world bathed in blood and purified by fire … Then we shall see.” For Zola, this advocacy of terrorism is a desperate sign of weakness and lack of confidence in collective action.

The powerful imagery in ‘Germinal’ conveys Zola’s sense of the dehumanising force of capitalist society. Men and women are denied freedom and human wholeness, subordinated to a logic which puts profit ahead of human need.

Zola said of ‘Germinal’:

“What I wanted to do was to cry out to the fortunate of this world, to those who are the masters: ‘Beware, look below ground, see those wretches who are working and suffering. Perhaps there is still time to avoid the final catastrophes. But hasten to be just, for otherwise here is the danger: the earth will open up and the nations will be swallowed in one of the most terrible upheavals of history.”

These were the words of a reformist, not a revolutionary; but he did include the possibility of social transformation in his perspective.

When Étienne leaves the village, it is not because he has abandoned hope in the working class, but because he had been offered a job in Paris by Pluchart, working for the First International. Since the novel was set around 1867, it was clear he was heading for the Paris Commune – it is therefore surprising that he doesn’t reappear as a mature and determined Communard in ‘La Débacle’.

Zola was influenced by one of the great socialist writers of his time, Jules Vallès, a leading activist in the Commune, exiled till 1880 in London. Zola helped him get journalistic work and encouraged him to write his powerful autobiographical novel trilogy.

Vallès had written articles about the miners’ strikes of 1869 and 1870 when the army was used against workers. On 12 March 1884 he participated in a public meeting in support of the Anzin miners. Later that year, Zola spent long hours discussing this with Vallès as ‘Germinal’ was being written.

During the 1984–1985 British miners’ strike, one British miner saw direct parallels between their experience and ‘Germinal’:

“There are many similarities between the events in the book and what is happening in the current miners’ strike. In both cases management provoked the strike deliberately, confident that the miners would lose, in order that they could reinforce their power. Both sets of miners put too much faith in one man. The French miners paid the price, defeat. Although the miners were beaten by lack of organisation, hunger and bullets, they were changed by the struggle. No longer content to accept their lot in life, the seeds of revolt were sown.”

(Quoted in Birchall)

L’Argent (1891)

‘L’Argent’ is the great novel of capitalist speculation. It depicts a period of transition from inherited assets such as land and property as the basis for wealth, to the more liquid and transferable intermediary of money itself. This ‘new money’ is less tangible, as it passes via scraps of paper through the hands of a new class of bankers, dealers and speculators, each skimming what they regard as their share where the game is played; the Bourse (Stock Exchange) and its side-markets. We also see the associated dispossession and humiliation of some of the decaying landed gentry who symbolise ‘old money’.

We get a sense of France’s expansionist and imperial ambitions with the Banque Universelle’s project to industrialise the near-East with apparently unlimited opportunities for exploitation, power and profit – all wrapped in terms of bringing ‘civilising’ Christian values to backward peoples.

‘L’Argent’ also takes us deep into the Paris slums, providing an insight into the living conditions of the poorest. We get a glimpse of the sordid Cité de Naples district with its open sewers and overcrowded hovels, a place of destitution and degradation and the flip side of the luxury and wealth of a minority. It is here that we discover the result of Saccard’s past sexual assault of Rosaline Chavaille.

‘L’Argent’ also doesn’t shy away from representing this antisemitism which ran deep across French society and Saccard’s prejudice against the Jewish banker Gundermann is visceral.

Another contrast is the ideological one between Saccard and Sigismund Busch, the visionary Socialist and former journalist colleague of Marx who now lives as an invalid with his money-lender brother. Sigismund is not a plotter, but an isolated intellectual working on schemes for a world without money or private ownership, reminding us of other Zola ‘idealists’.

Sigismund makes a cogent case:

“…the transformation of private capital… into social capital created by the work of all… Imagine a society in which the instruments of production are the property of all, in which everyone works according to their intelligence and strength and the products of this social co-operation are distributed to each and all…No more competition, no more private capital, no markets, no stock exchange…”

Saccard is appalled by the prospect, but doesn’t entirely dismiss it:

“What if this dreamer was right after all? What if he had correctly divined the future? He explained things in a way that seemed very clear and sensible.”

Sigismund goes on to outline how the concentration of capital could makes its future socialization easier. Addressing Saccard directly, he says:

“You’re working for us without realizing it… There you are, a few usurpers, dispossessing the masses, and once you are gorged, we, in turn, will only have to dispossess you… Every kind of monopolizing, every centralization, leads to collectivism… moving towards the new social order… We are waiting for it all to break down, waiting for the current mode of production to end in the intolerable disorder of its final consequences.”

The end of capitalism might not necessarily come through insurrection or violent revolution but as a result of systemic breakdown followed by a smooth transfer of power.

La Débacle (1892)

Written twenty years after the Sedan defeat and the Paris Commune, ‘La Débacle’ depicts the final collapse of the Second Empire. The greater part of the novel deals with the disastrous Franco-Prussian conflict, evoking the horrors of warfare. The final section dealing with the 1871 Commune, fails to do justice to the epic subject matter. Zola was sympathetic to the working class but had never been convinced of the need for revolutionary change.

Here was a revolution was taking place on his doorstep offering real emancipation from the regime which so disgusted him. Many artists and intellectuals joined the movement, and for 10 weeks Paris experienced what historian Georges Lefebre called ‘a festival of the oppressed’. It was the first time in history that workers had taken power and tried to build popular democracy, an attempt by working people to change their lives, live differently and actually achieve some of the demands which had until then been political rhetoric. The working class of Paris was reclaiming the Haussman boulevards from which it had been excluded.

But Zola was ambivalent, deriding the painter Gustave Courbet who was active in the Commune. He was a republican, not yet a socialist, and certainly not a revolutionary. He still had to supplement his income by working as a journalist. During the early weeks of the Commune he shuttled between Paris and Versailles, then stayed in Paris, finally leaving less than a fortnight before the massacre. He reported for two different newspapers – the republican ‘La Cloche’ based in Paris, and the right wing ‘Le Sémaphore’ of Marseille. As now, editors bought opinions, and Zola tempered his views in quite striking fashion to suit their tastes.

For the reactionary readers of ‘Le Sémaphore’ he writes: “Individual freedom and the respect due to property have been violated, the clergy is disgracefully persecuted, searches and requisitions are used as a means of government; that is the truth in all its shame and wretchedness. But it is not true that blood is running in the streets.”

But in ‘La Cloche’ he says: “… between Versailles, discussing wretchedly, and Paris which is reconciled at the ballot-box, I confess that instinctively I am for that great and noble city.”

The Commune ended with troops massacring thousands of workers in the ‘semaine sanglante’ of May 1871, thousands more were imprisoned or deported.

20-years later, with plenty of time for reflection and hindsight, Zola chooses to represent the experience of the Commune through only two characters, Maurice, sincere but naive, caught up with idealistic enthusiasm, and Chouteau, the violent and amoral turncoat, the most malicious of all Zola’s portrayals of leftist agitators and an unworthy representative of the values and ideas that animated the Commune. Neither does justice to the various tendencies in the movement, such as Blanquism, Proudhonism, neo-Jacobinism, Marxism.

We are left wondering why Zola never wrote a great novel of the Commune, the most significant political movement of his adult lifetime, happening right under his nose. Jules Vallès died several years before the publication of ‘La Débacle’. Had he lived to read it he would probably have been very disappointed.

Les quatre evangiles: Travail (1900)

Going beyond the Rougon-Macquart series, it is worth mentioning one of the ‘Quatre Evangiles’ novels Zola wrote later.

‘Travail’was Zola’s attempt to depict a socialist utopia. Luc Froment takes over a steel mill in a small town, and under the influence of Fourier’s ideas turns it into a workers’ co-operative. There followed the gradual development of a co-operative community and way of life, as people are drawn in by the sheer power of example. But Luc’s paternalism is the very antithesis of the self-emancipation of the working class. This benevolent Owenite ‘socialism in one town’ is imposed from above, and mysteriously seems to flourish within a hostile system and the rest of France makes no effort to obstruct it. Interestingly, Lenin is reputed to have liked this novel.

Several themes recur throughout the Rougon-Macquart novels and are exemplified by episodes and characters across the series:

- Class identity, the collective and the individual from ‘La Fortune des Rougon’, throughout the whole series.

- Speculation and profiteering, particularly in ‘L’Argent’ and ‘La Curée’

- Sexual exploitation, particularly in ‘Nana’ and ‘La Curée’

- Colonial exploitation in ‘L’Argent’

- Poverty and social mobility, upwards and downwards, particularly in ‘La Fortune des Rougon’ and ‘La Curée’

- Racism and antisemitism in ‘L’Argent’

- Idealism, utopianism, rebellion and gradualism: the influence of Marx, Proudhon, Fourier amongst others.

- Solidarity, strikes, rebellions, conspiracies and popular uprisings, revolutionary change, coups d’état, gradual change, growth, decline and degeneration, through a chain of characters from Sylvère and Miette via Florent, Sigismund, Étienne, Pluchet and Maurice and from the defence of the republic in ‘La Fortune des Rougon’ via the corruptions of capitalism in ‘L’Argent’ to Chouteau in ‘La Débacle’.

There are many connections between these themes and today’s struggles for social justice. Sadly, Zola’s radicals and rebels do not seem to grow in maturity as experienced activists or develop a more coherent political programme throughout the series.

The significance of Zola today

Zola was clearly a genius who redefined how working-class life, hopes, victories and defeats are depicted in literature. He gives the oppressed a greater voice and reveals social relations, agency and movements in their historical and sociological context better than anyone before him, showing how events are shaped by people’s circumstances. He understands that organised workers can contribute to history, even if he has reservations about some of the methods.

Zola was not a Marxist, but he was anti-capitalist; almost everything he writes is a denunciation of the greed, brutality, corruption and hypocrisy that characterised French capitalism in his day. He wants to present the whole of reality in the same way that we need to see society as a whole in order to understand the system we wish to change.

Nevertheless, even while describing successful independent working-class movements so brilliantly, Zola seems reluctant to show how this could transform the world and he tends to revert to individualistic psychological explanations of the motives and actions of working-class characters. In particular, it is notable that he chooses not to write a novel about the most significant political movement of his lifetime which he witnessed at close quarters. He is radicalized by what he sees and writes about, but is above all still a novelist, putting dramatic effect, individual character, personality and motivation at the centre of his work.

Based on a presentation to the Zola Society, London, 29 June 2023.

See also:

Zola’s ‘Money’ (January 2022)

Zola’s ‘La Curée’ and the corruption of desire (April 2021)

Sources:

Ian Birchall, ‘Zola for the 21st Century’ (2002) https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/birchall/2002/xx/zola.htm

William Gallois, ‘Zola: The History of Capitalism’, Peter Lang (2000)

Karl Marx, ‘Class Struggles in France 1848-1850’, ‘The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon’, ‘The Civil War in France’.

Thank you! I’ll devote some time to this, Eddie. Encyclopaedic! Is it OK to share? (I’m a former student on the Liverpool Uni continuing education sessions on European Literature in Translation; my classmates would relish this extra reading.)

LikeLike

Thank you Kevin, and feel free to share widely!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been reading Orwell’s* Inside The Whale and his analysis of writers of the early twentieth century. There’s an echo of your first paragraph above:

“But what is noticeable about all these writers is that what ‘purpose’ they have is very much up in the air. There is no attention to the urgent problems of the moment, above all no politics in the narrower sense. Our eyes are directed to Rome, to Byzantium, to Montparnasse, to Mexico, to the Etruscans, to the Subconscious, to the solar plexus — to everywhere except the places where things are actually happening. When one looks back at the twenties, nothing is queerer than the way in which every important event in Europe escaped the notice of the English intelligentsia. The Russian Revolution, for instance, all but vanishes from the English consciousness between the death of Lenin and the Ukraine famine — about ten years. Throughout those years Russia means Tolstoy, Dostoievsky, and exiled counts driving taxi-cabs. Italy means picture-galleries, ruins, churches, and museums — but not Black-shirts. Germany means films, nudism, and psychoanalysis — but not Hitler, of whom hardly anyone had heard till 1931. In ‘cultured’ circles art-for-art’s-saking extended practically to a worship of the meaningless. Literature was supposed to consist solely in the manipulation of words.” etc…

*In fact I’m re/reading everything by Orwell I can lay my hands on. He provides us with a reader for the Tory play book! (Noting the excellent piece in Saturday’s Guardian dealing with his misogyny.)

LikeLiked by 2 people