Joining the dots on system failure and climate justice in the era of global boiling.

July 2023 has been the hottest month on planet Earth in recorded history. It included the hottest day ever (6 July) and before it even ended, it had already registered the hottest 3 weeks ever.

United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres commenting on the global climate situation towards the end of the month, said:

“The era of global warming has ended and the era of global boiling has arrived… Climate change is here, it is terrifying…. It is still possible to limit global temperature rises to 1.5oC to avoid the very worst but only with dramatic, immediate climate action… All this is entirely consistent with predictions and repeated warnings. The only surprise is the speed of the change… The air is unbreathable, the heat is unbearable and the level of fossil fuel profits and climate inaction is unacceptable.”

A few of the facts:

- Global temperatures have risen by about 1.2oC since the industrial revolution. World leaders promised in 2015 to limit warming to 1.5oC by the end of the century, but current policies put us on track for a devastating 2.7oC increase.

- Average global ocean temperatures have broken records in May, June and July 2023, regularly approaching the highest sea surface temperature ever recorded.

- The Gulf Stream system could collapse as soon as 2025, with catastrophic climate impacts, severely disrupting the rains that billions of people depend on for food in India, South America and West Africa, and further endangering the Amazon rainforest and the Antarctic ice sheets.

- North Atlantic Ocean temperatures have been 4-5oC above average, meaning that marine organisms need 50% more food just to function as normal and qualifying as a category 5 heatwave which is ‘beyond extreme’.

- The area covered by sea-ice in the Antarctic is 10% lower than anything previously seen in July, with an area 10 times the size of the UK missing.

- Climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year by 2030, with direct health costs of $2–4 billion per year. Extreme heat in Europe last summer killed 61,000 people, with this year’s figure likely to be higher, but people in the Global South will be the least able to cope.

- Northern India has experienced its heaviest monsoon season ever with extreme flooding leading to at least 100 deaths and washing away bridges, buildings and roads. China is experiencing its second successive extreme heatwave with temperatures above 41oC in many regions. Forest fires have raged across southern Europe and Canada and extraordinary floods have hit Brazil, Spain and South Korea.

- The top five oil companies’ profits ($195bn in 2022), exceeding current spending on renewables and climate mitigation

There are many more shocking individual facts like these, each one a dispatch from the front line of global catastrophe. Taken together they tell a single story. We need to join the dots, make the connections and see the systemic big picture in order to address the whole rather than simply tackling each of its parts. We need to understand how our system is failing us if we want to have any chance of planning for a better one. The UN Secretary General’s words remind us that our politics has not yet risen to this challenge.

A few recent examples from the UK context:

- The government has recently announced the granting of over 100 new drilling licences to extract as much oil and gas from the North Sea as possible well beyond 2030, widely seen as a move which obliterates the UK’s climate commitments.

- Shell and BP each posted several billion pounds in profits in the last 3 months and continue to receive windfall tax breaks from the government. Shell’s investment in oil and gas projects for 2023 is predicted to rise by 10% and BP shareholders received £9 in buybacks for every £1 the company spends on ‘low carbon investments’.

- Only a handful of the proposals in Chris Skidmore’s ‘Mission Zero’ Independent Review designed to help meet Britain’s net-zero goals have been taken up by the government. A recent internal government audit found that many of the measures have been allowed to run off course, concluding that that their successful delivery now ‘appears unachievable’.

- Plans to electrify Britain’s railways are running so far short of what is needed that it could take 240 years to reach the net zero goal. At this rate, Britain is scheduled to electrify about 100 miles of track by 2025, just 12% of what is needed to be in line with net zero targets.

- The government seems to have abandoned any plans for a social energy tariff which would protect the poorest households faced with unaffordable energy bills or prepayment metering.

- A single by-election result is being read as a sign of a popular backlash against environmental protection. The government is reviewing ‘anti-car’ measures including low traffic neighbourhoods and low emission zones and political discourse is full of talk of slowing down or even rowing back on existing commitments.

It’s almost as if the status quo is sustainable. As if addressing poverty and redistributing wealth are not political choices. As if we don’t know that phasing out polluting energy systems and promoting public transport and active movement can lower the carbon emissions and air pollution which cause 7 million premature deaths globally per year.

At the same time, the demand to ‘just stop oil’ is derided and labelled as ‘extremist’ with both major parties falling over themselves to condemn climate campaigners and preferrring to focus on protest tactics rather than political substance. But the case for no more oil, together with that for a Green New Deal and a Just Climate Transition should be the political common sense of our age, because they will keep us within the survival zone set by the Earth’s planetary capacity. Some consensus about this could still allow plenty of room for debate about how best to achieve sustainability.

A just transition

It’s clear that we need to decarbonise as rapidly as possible and transition to a sustainable economy where we don’t consume planetary resources faster than they can be regenerated. And that can’t be achieved by simply replacing all fossil fuelled activity like for like or trusting in continuous overall growth in production and consumption. Given that inequality is growing and that the richest 10% of the population are responsible for half of all CO2 emissions, we need to reduce the overconsumption of that top tenth in order to address the current poverty, injustice and extreme inequality resulting from our economic system. This will also make decarbonisation easier to achieve in time to achieve our targets.

Climate justice means linking rapid decarbonisation with measures to ensure that the poorest do not carry the burden of change. It means ending all fossil fuel extraction and investing in the transition while also addressing the environmental consequences of growing inequalities and the overconsumption of the richest. Those who do the most damage can contribute the most towards both contraction and convergence without great discomfort. Global windfall taxes and wealth taxes could be used to fund investment in public transport, renewable infrastructure, energy efficiency and measures to reduce net consumption and end absolute poverty.

Faced with an existential global emergency whose causes we understand, the really pragmatic approach is surely not to continue the ‘business as usual’ which caused the problem, but to agree a rapid, coherent and co-ordinated global response at the necessary scale; applying known systems and technologies rather than hoping that untested, novel ones will kick in just in time. Instead, it feels like the ‘debate’ about climate action is being turned into another opportunity to score small shortsighted points, while ignoring the big systemic challenge.

Another ‘hottest month ever’ is over, but many more will follow – with lethal consequences. Antonio Guterres concluded his recent speech by urging leaders to lead: “No more hesitancy, no more excuses, no more waiting for others to move first.” But it seems we still have a lot more to learn about leadership in the era of global boiling.

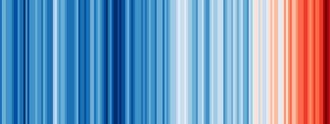

Illustration: warming stripes graphic published by climatologist Ed Hawkins. The progression from blue (cooler) to red (warmer) stripes portrays the long-term increase of average global temperature from 1850 on the left to 2018 on the right.

See also:

Climate justice, heat justice and the politics of resilience (August 2022)

Dilemmas of growth (June 2023)

Code red for human survival (November 2022)

Education, social justice and survival in a time of crisis (July 2022)

Owning our crises (March 2022)

‘The Ministry of the Future’ by Kim Stanley Robinson (December 2020)