What is work?

Work is organised and purposeful human activity, some of which is waged and commodified. How work is defined, who does it, how it is valued and organised, by whom and for whom and how it impacts on the world are important questions globally as well as contributing to our personal and social identities. Our understanding of work needs to include production, reproduction, distribution, subsistence and service work, caring for people and planet as well as unremunerated work.

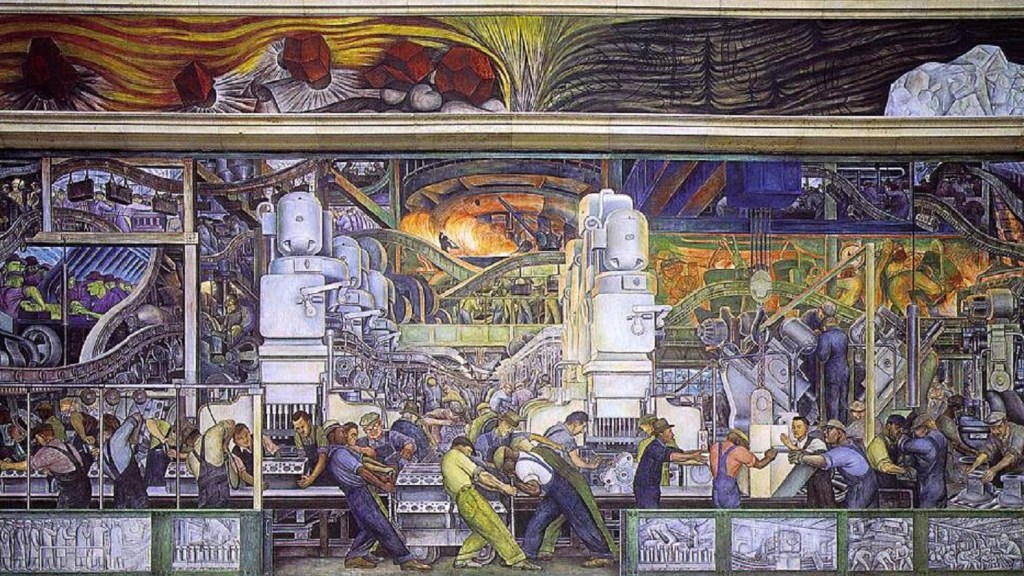

Diego Rivera, Detroit Industry Mural, 1933

Work is a means for the collective transformation of the world as well as a source of meaning and a long-term commitment. The nature of work and the distribution of its burdens and benefits are shaped by the institutions and patterns of wealth and power which humans have created. Work processes reflect our wider systems of economic and social relations and are often contested and the subject of political struggle.

The multiple challenges we face; the climate and planetary emergency, the crisis of growing inequality, global conflicts and injustices, can all be seen as symptoms of a single crisis of capitalism. Any project aiming to go beyond the logic of capital accumulation towards an economy organised around human needs and social justice within planetary boundaries is necessarily also aiming to go beyond capitalism.

In capitalism, the terms of work are set by capital, and in making the transition to a post-capitalist economy we would need to re-evaluate, reconceive and reorganise work on terms of sustainability, justice and freedom. We would need to consider the quantity, distribution and quality of work and to place the skills needed for democratic planning at the heart of the transition process.

Work under capitalism

In capitalism, people’s labour is seen as a means to expand profitable production and consumption linked to the imperatives of growth and capital accumulation. Meeting human needs, creating good secure jobs, ensuring greater equity or sustainability are not key objectives. Instead, the aim is to maximize the return on investment and keep costs down.

Workers are regarded as ‘human capital’ and encouraged to see themselves as tradeable commodities in the labour market. Being successful requires them to invest in themselves by acquiring the best possible skills and qualifications to compete against other workers in an ever-accelerating race to be more attractive to potential employers and justify their share of labour costs. The ‘gig economy’, as the ultimate neoliberal labour process, promotes a toxic culture where workers have little security and few rights, and their survival depends on their ability to ‘hustle’ on their own account and provide exactly what their clients want, when they want it.

The way work is organised is not primarily aimed at creating coherent, fulfilling or satisfying jobs for workers. Within job roles, tasks and associated skills are often fragmented and packaged in reductive ways. Job specifications, work hierarchies, ‘skilled’ and ‘unskilled’ categories, pay differentials, notions of routine, managerial or ‘creative’ roles are all the result of socio-historical processes which reflect the power of employers to determine work processes and relations. Many systems of evaluation and reward encourage individual workers to see themselves in competition with colleagues as work becomes another arena for competition, recognition and advancement.

The result is that much contemporary work fails to meet workers’ basic material needs or accepted norms of justice, freedom, and democracy. Britain’s labour market, like many others, is characterised by insecurity, precarity, punitive surveillance and wages that often can’t support the basic needs of life. The experience of work is often one of dominance, exploitation and alienation as the introduction of new technologies and processes, restructuring and downsizing of workforces reinforce climates of fear and precarity and consolidate existing inequalities.

In the labour market ‘capital commands and labour obeys’, and the needs and aspirations of workers and consumers are unlikely to be fully met. Like any other market, it will tend to reinforce inequalities because it is driven by the need for accumulation and concentration of capital. At an individual level we experience work through relations of production and consumption. There is also the unremunerated work of reproduction and care (and arguably that of the non-human living world) – the ‘work which makes all other work possible’ and falls outside the market while being crucial to its functioning.

Many people are trapped in low-quality jobs with insecure wages. Youth unemployment across Europe is over 14%, reaching beyond 40% in some regions. This shameful waste of human potential undermines the creativity of the workforce and endangers prosperity and wellbeing. In the case of Britain, the 2019 report of the UN rapporteur Philip Alston makes the position clear: “Low wages, insecure jobs and zero-hour contracts mean that even at record employment there are still 14 million people in poverty… Britain is not just a disgrace, but a social calamity and an economic disaster all rolled into one.” (Alston, 2019).

While legislation and the regulation of wage labour can mitigate the worst excesses of exploitation, the basic conditions of work are often gendered, racialised and highly unequal. But the workplace can also be a site of education and politicization, where people meet and share ideas, imagine better futures and can mobilise to improve things. Workplace organisation gives workers a voice and the power to negotiate better conditions or an increased share of the surplus or other workplace changes. The work of trade unions is often defensive; preserving pay differentials or protecting relative privileges, but unions can also provide opportunities to develop new conceptions of work and economy.

If we are to look beyond capitalism to an economy aligned with human needs and planetary sustainability, we need to question the dominance of market relations and the notion of workers merely as human capital.

Work beyond capitalism

Questions about the nature, value and distribution of work are central to the debate about any post-growth society which aims to promote social justice and sustainability. A transformation of the basis of economic decisions will also require a transformation of the way work is organised. We will need to break down many of the distinctions and hierarchies of work: ‘unskilled’, ‘blue collar’, ‘middle class’, ‘graduate’, ‘precarious’, which are the result of choices about how to define and configure work.

Kate Raworth’s ‘doughnut’ model (Raworth, 2017) proposes a ‘safe’ range for global resource use and environmental impact and this corresponds to a sustainable and equitable level of economic activity. To ensure human survival, we need to aim for this across all the key indicators. The ‘sweet spot’ for work would represent the total amount of work needed to sustain a good life for all humans on Earth while staying within the ‘doughnut’ and not exceeding key planetary boundaries. That work should be shared as equitably as possible with remuneration pitched somewhere between a universal living wage and a maximum wage. Such an aspiration would avoid the need to set organisational pay ratios, as everyone would be somewhere within the safe range.

Such a reconceiving of work will require concerted planning and democratic participation. Such an economy will need to be democratically shaped and this will require planning at all levels. Collective knowledge, skills and capabilities will be the tools for creating sustainable and socially just economic and social relations. These will include amongst others, skills of analysis and reflection, democratic deliberating and decision-making, organising and mobilising, identifying and resolving conflict. These are not ‘elite’ activities to be reserved for a few, they are skills which will need to be developed, shared and exercised widely.

A democratic post-capitalist economy could draw on experiments in participatory economics and popular planning such as those of the Doughnut Economics Action Labs (DEAL, 2023) and Community Wealth Building programmes (Brown and Jones, 2021). Experiences of worker-initiated planning in England include the Lucas Workers plan in the 1970’s which started as a defensive trade union response to plant closures and job losses and became a fully developed alternative production plan based on socially useful production (Wainwright and Elliott, 1982). Worker owned co-operative groups like Mondragon in the Basque Country, founded in 1956 and still operating successfully, also offer glimpses of the liberating possibilities of work in a democratically planned post-capitalist economy.

The quantity and distribution of work

It seems that a future economy could operate with less human labour overall. The technologies of the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ and the potential of big data and machine learning bring new productivity gains and put jobs at risk in many sectors. We can plan for this in an equitable way and achieve a reduction in overall working time via a redistribution of the surplus value resulting from increased productivity.

This productivity increase impacts in some sectors more than others. Ben Gallant distinguishes between ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ sectors of the economy, corresponding roughly to productive and service work, and describes the employment productivity problem (Gallant, 2023). This flows from the fact that in a low- or no-growth economy, increased productivity in the ‘fast’ sectors where automation and efficiency gains have the greatest impact, can lead to more unemployment as fewer workers are needed to produce the same output. The classic response is to produce more and ‘go for growth’, thereby maintaining employment levels. But a more sustainable solution is to share the benefits of fast sector efficiencies by shifting employment towards ‘slow’ service jobs and reducing working hours across the economy.

Service-based activities tend to be labour-intensive because their purpose is based on the time people spend engaging with others in care or in craft. They are also generally less resource hungry. The economic value of health, care and therapeutic work, teaching, social work and hospitality is generated mainly through human contact rather than increased material production or consumption.

The shift towards more labour-intensive services could allow for both higher levels of employment and reduced working time. We would have to accept lower labour productivity growth overall, but we would benefit from the double dividend of higher employment and lower environmental impact.

Productivity is not merely an economic concern but also a political one, touching on the quality of work, the need for human agency and the limits of automation. The politics of time is also a politics of freedom. Working less means gaining free time to be used as we choose, and becoming time-richer needs to be combined with the availability of more ‘quality time’ activity for people to be able to engage in self-development and community development.

If we can de-link employment from subsistence income, we could achieve a shorter working week and working day for all, with economic security underpinned by a universal basic income. Writing over 30 years ago, André Gorz made the case that it was no longer possible to continue to link people’s incomes to the quantity of work needed by society. For Gorz, this was liberating; establishing everyone’s right “to earn their living by working less and less and better and better, while receiving their full share of the socially produced wealth and the right to work discontinuously and intermittently without loss of income, in order to open up new spaces for activities that have no economic ends and grant these a dignity and a value for individuals and society…” (Gorz, 1991)

The work which has to be allocated and shared at different levels will vary from place to place and the processes need to be transparent and contestable. There will be many political questions to address around the sharing of work and the current disproportionately gendered and racialized distribution of work, including unremunerated work.

The quality of work

As well as questions of quantity and distribution, there are also questions of quality. Working means more than just doing what is required of us in our contract of employment. At work, we experience sociality, solidarity, collectivism, the exercise of power and subjection to power and the closing off or opening up of new possibilities. Work continually changes us and educates us.

Work is never purely instrumental; getting the job done is also an emotional and social process loaded with meaning. We cannot assume that workers, or consumers, think or act as purely rational economic agents. People do jobs, commit to jobs or leave jobs for a multitude of complex and interacting social reasons which are not easily quantified.

What is good work? How do we measure the value of work, the worth of different jobs? Workers want to feel they are doing something necessary and useful, helping to meet human needs and aspirations, making meaning and finding purpose, contributing to human wellbeing. If, in a more egalitarian society, there is still some need for physically demanding, high-risk or repetitive work, we might choose to mitigate this by enhancing the variety of tasks or planning for less working time or more pay in consultation with workers themselves.

We need to make the case for changes to the quality of work as part of any economic transition. As suggested by Amy Isham, this would include valuing the quality of our experience as opposed to our material consumption (Isham, 2023). A more collective experientialism would value the benefits of collaborating with others and participating in building community and democratic decision making.

The fundamental expectation that work should help to meet human needs means prioritising work that builds community, solidarity, resilience, democracy and sustainability. This suggests more investment in work which supports care, justice, reparation, regeneration, restoration and reuse as part of a more circular economy. These priorities do not require us to go backwards or deny technological change. While keeping historic craft skills alive is a worthwhile aim, we don’t need a wholesale return to pre-industrial ‘slow’ modes of production.

Robin Hahnel reminds us that good work should be attainable for all: “We should never forget to point out that what every citizen deserves is a socially useful job with fair compensation. We should never tire of pointing out that while capitalism is incapable of delivering on this, it is just as possible as it is sensible.” (Hahnel, 2002).

David Graeber suggests that capitalism cannot foster true innovation because it tends to apply new technologies in ways which embed existing forms of labour and suppress the idea of any radically different technological future which might “let our imagination once again become a material force in human history.” (Graeber, 2015)

Rethinking work: democracy, social justice, sustainability and planning

The transition to a more sustainable and socially just economy will require people to take control of work as part of taking control of resource use and distribution, operating within set boundaries at every level, from the global to the individual. This will only be achieved consensually if combined with a high degree of democratic decision-making at every level, with as much autonomy and devolution of power and respect for local specificities as is consistent with planetary limits. Highly developed democratic and planning practices will need to be in dynamic equilibrium. Power to make decisions and take action will flow both ‘upwards’ and ‘downwards’ and there will be different approaches to development, innovation and work in different contexts and to meet new demands generated by different groups of people.

Examples of current proposals to redesign work include:

The transformation of work outlined by the authors of ‘The Future is Degrowth’ (Schmelzer et al, 2022):

- Phasing out of unnecessary and wasteful work.

- The automation of alienating work.

- Access to good, non-alienated and meaningful work for all.

- A radical reduction in working hours without lower paid workers losing income.

- A more equal distribution of work.

- A valorization of reproductive and care work.

- Collective self-determination in the workplace.

- Stronger workers’ rights and autonomy.

The section on ‘Reforming Work’ in the text ‘The Sustainable Economy We Need’ adopted by the European Economic and Social Committee of the European Union in January 2020:

“Work is more than just the means to a livelihood. Good work offers respect, motivation, fulfilment, involvement in community and in the best cases a sense of meaning and purpose in life.

“Specific policies for in-depth consideration and further work could include:

- enhanced worker representation on company boards,

- the adoption of a right to work or “job guarantee”,

- universal basic income,

- universal basic services and

- a maximum income.”

The three principles proposed by the Centre for Democratising Work initiative of Common Wealth (Lawrence, 2023) as a route forward; democratisation, decommodification, and decarbonisation:

- Democracy, because labour is a profound commitment; of our time, our bodies, our minds, the conditions of which should be subject to democratic determination and meaningful agency.

- Decommodification, because human beings are not commodities and work should not be treated as such.

- Decarbonisation, because the fundamental collective task before us is securing a just transition to a post-carbon future of genuine equity and sustainability.

These agendas offer a direction of travel which requires some reimagining of the conditions for waged labour and a reshaping of power at work. As a minimum they require us to start moving from Labour Market to some kind of Labour Plan and to extend our ideas of living well within limits to working well within those limits. This could be the beginning of a decommodification of work, de-linking it from the means of subsistence and to ensure material security for all regardless of employment status.

We will need to develop more democratic, collective economic decision-making about what needs to be done and how much resource we can allocate to meeting each human need, and a level of planning which requires more socialized investment with decisions taken in the public / political sphere, so that our collective intelligence can be translated into actions to develop the infrastructure and jobs we need. We will also need to value and develop those skills associated with human flourishing and good work. These will have a collective dimension rather than being purely about developing individual ‘human capital’.

The task of advocating and realising a post-capitalist economy needs to be initiated by workers themselves and advanced through broad campaigning which connects economic, social and environmental demands and aspires to be majoritarian and win elections across the globe. As this movement grows, it must keep alive the idea that our current economic relations are not inevitable and that another world really is possible.

Sources:

Alston, P. (2019) Visit to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland : report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, United Nations https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3806308?ln=en

Brown M. and Jones R. (2021) ‘Paint Your Town Red’, Repeater Books.

Doughnut Economics Action Lab – DEAL (2023) https://doughnuteconomics.org/

The European Economic and Social Committee (2020) ‘Reforming work’ in ‘The Sustainable Economy We Need’. https://www.statista.com/statistics/266228/youth-unemployment-rate-in-eu-countries/. https://www.cusp.ac.uk/themes/s2/wp12/ ; NAT/765 – EESC-2019-02316-00-01-AC-TRA (EN) 10/14

Gallant, B. (2023) ‘The Future of Work?’ MSc. Ecological Economics module lecture notes, University of Surrey. https://surreylearn.surrey.ac.uk/d2l/le/lessons/240558/topics/2711983

Gorz A. (1991) ‘Capitalism, Socialism, Ecology’, Verso.

Graeber D. (2015) ‘The Utopia of Rules’, Melville House.

Hahnel R. (2002) ‘The ABCs of Political Economy’ Pluto Press.

Isham A. (2023) ‘More fun with less stuff’ MSc. Ecological Economics module lecture notes, University of Surrey. https://surreylearn.surrey.ac.uk/d2l/le/lessons/240558/topics/2712470

Lawrence, M. (2023) Centre for Democratizing Work https://www.common-wealth.co.uk/centre-for-democratising-work/introducing-the-centre-for-democratising-work

Raworth, K. (2017) ‘Doughnut Economics’, Random House.

Schmelzer, M., Vetter A., Vansintjan A. (2022) ‘The Future is Degrowth’, Verso.

Wainwright H. and Elliott D. (1982) ‘The Lucas Plan’, Allison and Busby.

See also:

A broader view of skills (June 2023)

Dilemmas of growth (June 2023)

Debating growth (November 2022)

Learning, earning and the death of human capital (February 2021)

Primo Levi on work and education (May 2016)

‘Useful work v. useless toil’ by William Morris (December 2014)

Thanks, Eddie. So much to ponder.

Rethinking work in this way also requires rethinking how we challenge global capitalism. Thank you for providing so many references and elements to this.

If corporations can determine wages and conditions internationally, unions must also operate at home and away. Just as rail workers in struggle need to (and do) support striking health workers in this country, it’s more important than ever that a dispute in one country elicits active support from workers in the same company/industry abroad.

Pickets should not stop at factory gates. There’s a good history of this amongst seafarers and dock workers, and a growing awareness of their potential power by those employed in (sometimes in franchises) US outfits like Starbucks and McDonald’s.

As you note, too often an apparent innate or defensive conservatism amongst trade union leaderships has restricted this, and it’s encouraging to see rank and file organisations developing in sectors with traditionally weak union membership. https://www.ft.com/content/576c68ea-3784-11ea-a6d3-9a26f8c3cba4

We must be realistic. Capital will not easily relinquish its grip. In fact recent post-Brexit developments give further grounds for pessimism. For example only, the Tory Trans-Pacific trade deal, like its Brexit progenitor, will patently damage the UK economy. That’s not where the loyalties of our governors lie. The (current) prime minister retained his American green card whilst notionally a UK government minister. One of his predecessors (the one who urged Ulez on London and then said the opposite, the one who told us to isolate and then partied) swung in a more easterly direction (at least until he saw which way the wind was blowing) https://voxpoliticalonline.com/2022/03/06/johnsons-sanctions-hesitation-lets-russians-make-423-million-after-invasion-of-ukraine/

Their hearts belong to Daddy Bigbucks.

Good work? The common good? Climate control? Social housing? Universal healthcare? Public education? Of course they cost. But any rational long-term view of the world demonstrates that not providing them is far more costly. We can demonstrate this but how do we prevail?

Call me an awful pessimist (but, honest, only of the intellect!); I see our current crop of would be world-bestriders more like O’Brien in 1984: “Never again will you be capable of love, or friendship, or joy of living, or laughter, or curiosity, or courage, or integrity. You will be hollow. We shall squeeze you empty, and then we shall fill you with ourselves.”

As so often you provide an awful lot of excellent suggested reading, and now thinking about that unearths this. To be digested when I’ve finished Animal Farm… 😉https://libcom.org/article/challenging-global-capitalism-labor-migration-radical-struggle-and-urban-change-detroit-and

LikeLike